Capturing the World One Image at a Time

Photographs are more than images created by seamlessly joined pixels or lifted from film that mark important moments in life. They are our connection to the world around us. Each day, thousands of photographs are taken illustrating family vacations, dinners with friends and, of course, the ubiquitous “selfie.” Photographs can be taken by oneself and shared via social media. Or, they can be taken by professional photographers and placed in cherished albums. They are used as screensavers and adorn nightstands. They are viewed through countless pages of magazines and splashed on billboards. Newspapers hire photojournalists specifically for this purpose to illustrate to us and connect us with the world in which we live. It is a dangerous job — often times fraught with peril. It is a difficult job to painstakingly capture the moment perfectly for the ages. It is a rewarding job to understand the significance of the shot taken. No one understands the job better than Kimberly Allen-Mills. Allen-Mills has shot for many internationally acclaimed broadsheets — The Sunday Times of London and The Independent to name but two.

Images are powerful. Some of have spawned revolutions while others have promoted peace. Many have captured flawless beauty while others demonstrate raw ugliness. While the viewer of the image concentrates on the subject, often times, what is left un-regarded is the man or woman who has risked life (and sometimes limb) to bring the shot to the page. And, sometimes, life behind the lens is as interesting a subject as that which is being recorded through the lens.

“We were in Kashmir,” begins Allen Mills, “covering demonstrations against India. All of the journalists were staying together in one place and we heard a story about a group of demonstrators that had been fired upon. One demonstrator had pretended to be dead and survived and had been able to get to us to tell his story. Very early the next morning, we were woken up by officers banging on our doors in the hotel, telling us to get up and outside to a bus. They were trying to confiscate any film, pulling it out from the canister to expose it. We were put on the bus, driven to a plane waiting on the tarmac at the airport and sent back to New Delhi. I just remember the fear in the faces of the young army officers carrying their guns while they were getting us on the bus – fear, guns and confusion are a very scary mixture.

A good photojournalist understands that capturing an image is not just about the subject itself. It is about the use of cameras and other equipment, the creativity of thought in finding the right story to tell and the skills in bringing that story to life in two-dimensional form. It is an inherent love and, from a young age, Allen Mills nurtured it.

“For as long as I can remember,” she says, “I have been drawn to images for their ability to immediately deliver a message without words and transport you to another place. I am a visual learner and rely heavily on images for my information. I bought my first camera by selling seeds around my neighborhood when I was twelve years old. It was a brownie instamatic and I think that I still have it in a box somewhere. My high school had been newly built and they included a dark room – I took photography class and spent hours in it. I built pin hole cameras and was fascinated by the process of capturing an image, even without a lens, and I still love watching a black and white image appear, as if by magic, in the developer tray.”

Allen Mills concentrated on her journey as photojournalist shortly after meeting the man who would become her husband. After graduating from Emerson College and the University of Massachusetts, she studied, worked and acted at HB Studio, a professional acting studio in Greenwich Village, New York. The director of the studio introduced her to a British journalist and it was Kismet.

“I had not been able to do a lot of photography since I moved to New York to act,” she says, “but his interest in photography brought me back to it. I took several professional photography courses at the International Center for Photography in New York and, early in 1986, a former journalistic colleague of his asked him to join a new newspaper that was created called The Independent. He agreed to join and to establish the South African bureau and we arrived in Johannesburg just after the South African regime cracked down on the anti-apartheid movement. A state-of-emergency and been declared and more than 25,000 people were arrested.”

After three years covering the rule of apartheid in South Africa, the team moved through the world covering the hottest stories of the time. They moved to India and joined the Sunday Times of London, then lived in Berlin where they covered the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reconstruction of Germany and Europe. In 1992 Paris called and then New York in 1995. After moving back to Paris again in 1998, Allen Mills would eventually return to the United States in 2002, settling in the Washington DC area, with her two daughters.

Throughout this era, Allen Mills captured not only photographs for the world to see but, also, personal experiences that she would carry for life. Some illustrate the beauty and grace of the human spirit during times of tumult and grief. While others exemplify the adage “life goes on” even when living under extraordinary duress.

“There was a township of people that had been forced out of their homes and were living in a squatter camp on a strip of land between two highways,” says Allen Mills, “they had been told to leave and had fled before the bull dozers razed their homes to the ground. They were being moved into one of the new “homelands” in order to strip them of their South African citizenship. They had taken what they could carry – many of them had full households with beautiful antique dining sets, china tea sets, silver – and had built a camp of shelters made of plastic sheeting, salvaged wood, pieces of highway signs. In one of these plastic bag huts, we listened to a woman tell us what had happened to her. As she spoke, she opened a Marks & Spencers Christmas cake and served it to us on beautiful china plates. I don’t know for what special occasion she had been saving that cake but I have never felt such gracious hospitality.

In Israel during the first gulf war, scud missiles were fired and the threat was that they would have gas attached to them. Everyone had a gas mask, and when the sirens would go off, people would put their masks on and continue what they were doing. In the restaurants guests would finish their meal and their wine with their gas masks on.”

One story that Allen Mills covered extensively were the events that transpired on Tiananmen Square in June of 1989. After images of the student protestors beamed across the planet, she shot and spoke with everyday Chinese in the streets paying close attention to their stories, the official line and the international responses. Here, she also got to partake in another interesting experience that would create a lifetime memory.

“In 1989, we were in Beijing for three months to cover the aftermath of the Tiananmen square protests which resulted in military suppression and the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of civilian protestors. We had two televisions in the hotel room, one on a western news station and one on a Chinese news station, showing the same images but with two opposite explanations. The story being told there was that the students in the square had become violent and attacked the police – they had mother’s of soldiers crying and statements from alleged witnesses – it was frightening to watch government misinformation in action. We spoke with some Chinese citizens in a park that was noted in the guide books as a good place to meet with Chinese students who were learning English and they were all convinced that the reports about what happened in the square were totally fabricated by the western media. All the while we were speaking with them, there were men with black arm bands walking through the crowd, listening.

As a journalist, many times you are going into an area when everyone else is rushing to leave. That was very noticeable in China after Tiananmen Square, all of the tourists had left so we saw the Great Wall and the Forbidden City completely empty. There was a very popular shooting range outside of the city where you received what looked like a restaurant menu with every type of weapon imaginable listed – hand guns, mortars, ground to air missile launchers. You simply checked off what weapon you wanted to try and they would set you up. Because there were no other customers, they let us try everything and we spent a day blowing up stacks of bricks on the hillside.”

Of course, the casual viewer of a striking image does not often think of the journalist shooting the photograph. For a good photojournalist, this is an intentional act and carries through to subject itself.

Allen Mills says, “You try and disappear and make them forget that you are there so that you get the reality and not what they think they should show for the camera. If you can achieve that, you can watch what is happening and try and feel the rhythm of what is happening so that you can capture those moments of truth.”

And, that is what is so special to Allen Mills and that which she enjoys most.

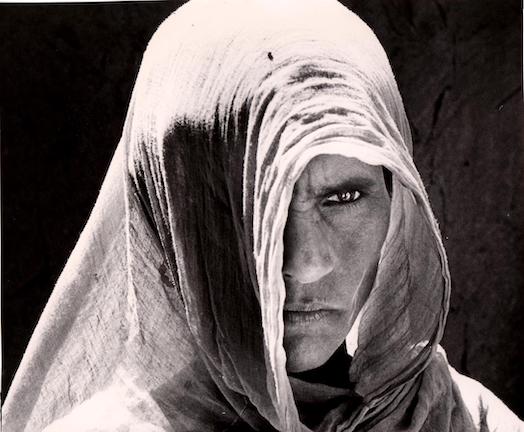

“Being able to be a witness to people’s lives, being invited to see and hear people’s stories, many times at the most critical or catastrophic times of their lives and then being able to retell their story to a wider audience in order to hopefully help or have some positive influence on the outcome. And, with photographs – when you see an image – you see the faces, the body language and the look in the eyes of the people. It is easier to immediately feel what they are experiencing, to empathize, and harder to forget, to move on, to not be moved in some way.”

From the thousands of images that Allen Mills has shot, many stand out for her as personal achievements. And, she does have a favorite. She also has a fascinating anecdote from her life as a photojournalist.

“Even though it is a very sad and disheartening story, my favorite image is of the mother in India whose daughter was killed. In the face of unimaginable grief, anger and despair, she remained strong and continued to fight for justice for her daughter.

When we first moved to South Africa, we were invited to a New Years Eve party at the home of a journalist in Soweto. We had to hide in the back seat of his car to get in and out because, as white people, we were not supposed to be in the townships. It was a wonderful evening full of music, dancing, food and drink. In the midst of the celebration a young businessman told us his story of two months before, having been dragged out of his car and beaten unconscious while his fiancée was put into the trunk and the car lit on fire by a group of white youths who assumed he had stolen the car – it was a BMW. At the end of the night, as we were driven out of Soweto, we passed an abandoned check point that the Camrades had set up and the tires were still burning. We were lucky.”

The life of a photojournalist is both exciting and fulfilling. While shooting in dangerous locations shots of adrenaline invade the system and the personal anecdotes and stories provide entryways into the human condition. But, it is never predictable.

“There can be a lot of “hurry up and wait” sometimes depending on what type of story you are covering. But, sometimes you walk in and just start shooting images. Sometimes, you need to wait and watch to understand what is happening and what is important and how you can capture it.”

These days, Allen Mills has taken a break from roaming the world looking for the pinnacle shots. She spends time with her daughters, who have taken on their mother’s interest in creative fields. Allen Mills enthusiastically declares, “I am very proud of my two beautiful daughters. One who is pursuing photography and the other who is pursuing theatre. I am glad that they share my love of these two art forms.” And, she works downtown for an international hotel chain where she remains exposed to myriad global denizens. Many of these people who have emigrated from regions she has lived or covered.

With so many facets of her life, Allen Mills is equally proud of its constant theme. “If there is a single thread that runs through all of my life experience it is a passion to understand people, their lives and struggles and to try and help by getting their stories out to a broader audience.”

Such is the role of a great photojournalist.

1. Mother in India: This image is of a mother whose daughter, the beauty of the village, had caught the eye of one of the government officials. When the girl spurned his advances, he raped, murdered and left her on the ground in the middle of the village. Everyone knew that the official had committed this heinous crime but no one would arrest or charge him.

2. Bhopal India: In December 1984 there was a deadly gas leak at the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal which rolled through the shanty town were the workers lived and killed thousands of people, many in their sleep. Survivors and family members who still live there are dealing with the serious health issues caused by exposure to the gas. We met an 11 year old boy who had to have an emergency heart and lung operation after the gas leak in order to save his life.

3. In the townships, there was suffering but there was also such life and a sense of humor in the face of violence and oppression. In Muncieville, the township where Arch Bishop Desmond Tutus grew up, boys played with an old gun they had found.

4. A group of people had been forced out of their homes and were living in a squatter camp on a strip of land between two highways – they had been told to leave and had fled before the bull dozers razed their homes to the ground – and were being moved into the Ciskei, one of the new “homelands” in order to strip them of their South African citizenship.

5. In Beijing, there were men posted throughout the city with black armbands, waiting for people to come and report the names of anyone who had been in Tiananmen Square that night. The state of emergency that had been declared included a ban on taking photographs so all of the photojournalists had resorted to taking photographs through the windows of vans. While walking through the city one day, we encountered an informant in front of a fast food restaurant. By acting like a tourist excited to find a Kentucky Fried Chicken, I was able to take this photograph.

This story previously ran in the February 2014 issue of John Eric Home. We have re-printed the feature exactly as it ran in that issue.